Over 600 years of organ culture

In this free Hanseatic city of Hamburg there are more harbors, ships and bridges than those in Venice and in Amsterdam combined. But organs? Even the people who believe they know the city well enough are astonished with the fact that Hamburg exceeds Paris in the number of organs in its city center. This unique significance of international organ culture began centuries ago and is still present, unbroken.

Undiscovered treasures of Hamburg: over 300 organs from different eras

There are more than 300 instruments throughout Hamburg – not only in churches, but also in concert halls, schools, hospitals, retirement villages, prisons and even in private households. And we are not just talking about electronic organs but the traditional instruments, whose sound is produced by pipes.

What is even more special than the large sum of instruments is the extraordinary quality in which these instruments are maintained: the St. Jacobi’s organ, completed in 1693, belongs to one of the most substantial achievements of the ingenious master Arp Schnitger, whose 300thanniversary of death is celebrated in 2019. And Hamburg owns this very special, valuable and beautiful sounding baroque organ. For a long time, and even now, Hamburg is a pilgrimage destination for organ experts and enthusiasts from all over the world. More than a dozen of Hamburg organs is outstanding in this manner and are considered among the experts to be the pinnacle of their respective era.

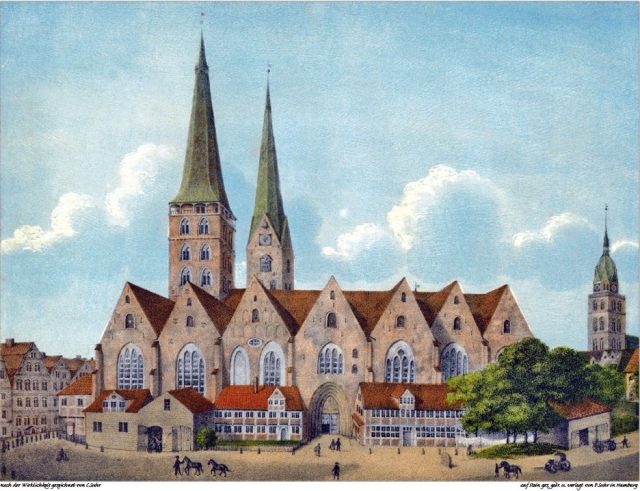

Thanks to the trade, Hamburg had achieved an unprecedented wealth in the early days – and they desired to express that. Therefore, not only they built themselves a new city hall, but they also built a rather modest yet representative Mariendom, major churches such as St. Petri, St. Katharinen, St. Jacobi and St. Nikolai, all with powerful towers, which not only testified the fear of God but also represented the civic pride of their builders.

And anyone who went to church in Hamburg was already able to encounter organ music. There was a proof that in Mariendom an organ existed from as early as in 1358, which the Franciscans ordered in their Maria Magdalenen church, in which two of them stood in the area of today’s chamber of commerce. It is believed that all major churches probably had at least one organ in the time before the Reformation, which were all produced in this city. In the 15thand early 16thcentury there were at least seven organ builders within Hamburg. The names include Harmen Stüven, Jacob Iversand, Hans Lüders, Domenicus Engelbert, Meister Marten and Meister Johann. Sometimes the organ builders were also organists themselves, such as Johann van Kollen, who in the middle of the 15thcentury built the organ in the church of St. Petri, and simultaneously was an organist under contract.

The Gothic organs were still relatively simple in its technique, the so-called Blockwerk had no stops which you could play separately. The music was not considered as an accompaniment to the congregational singing yet, but worked within the interplay of worship as a counterpart to the liturgist, the choir and the congregation. In the late 15thand early 16thcentury building of instruments continued to develop, but with the Reformation it was initially unclear whether the organ would be compatible or even suitable to the new faith and new worship practice. While the reformers Calvin and Zwingli decided against the presence of organ – analogous to the iconoclasm – which even came to the destruction of organs, Martin Luther promoted after initial hesitation, the liturgical use of the organ.

After the Reformation it really opened up in Hamburg

In the course of Reformation, which in the North went very well, thanks to the prudence of Johannes Bugenhagen, not a single organ was destroyed nor damaged in Hamburg. On the contrary, it rather lightened up: Foreign organ builders from Flanders, especially from the Duchy of Brabant, came to northern Germany and settled in Hamburg.

The competition grew in size, soon there were companies with excellent reputation, such as the family business Scherer, who built over the generations ever more modern instruments which enhanced their own reputation. Already at that time there were superregional relations and connections, for example between north and middle Germany. Gottfried Fritzsche, who had been an Electoral Saxon court organ builder since 1614, first moved to Wolfenbüttel and Celle before settling in the former Hamburg district of Ottensen in 1629. He succeeded Hans Scherer d. J. He could not complain about the lack of work, so he received the lucrative order to renew the aging organs of the four major churches.

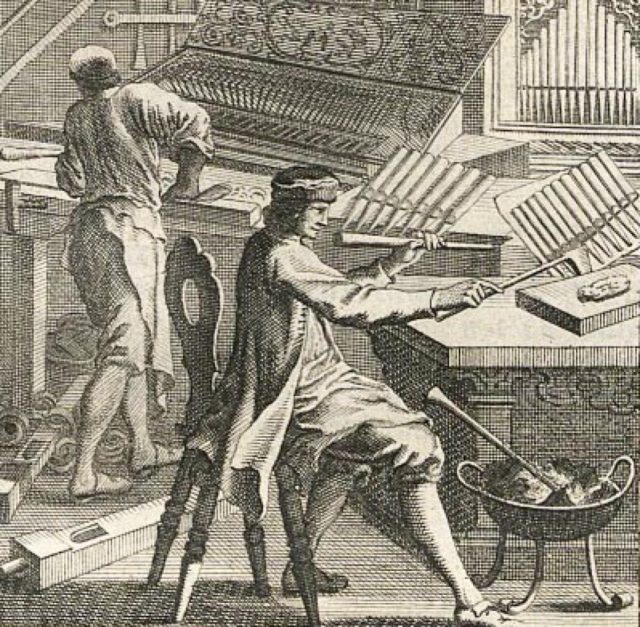

The organ concert was in business in Hamburg

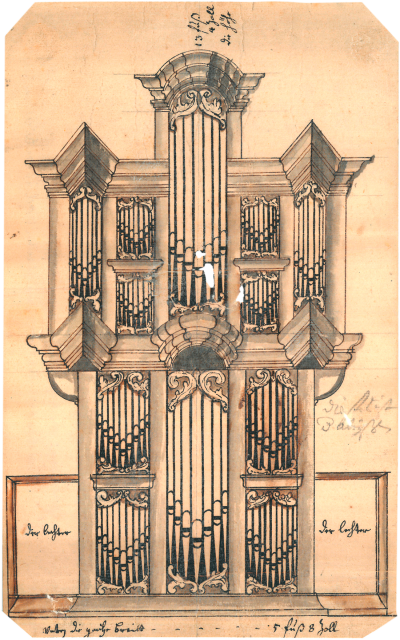

From the beginning of the 17thcentury, organ building developed dynamically, and thanks to the development of new stops, the sound quality became even more sophisticated and richer, which opened up the new compositional and interpretative possibilities completely. With Arp Schnitger, who was born in 1648 in Unterweser and moved to Hamburg in 1680 and established his main workshop there, a new blooming of organ building began, which affected enormous parts of northern Europe. In his workshop Schnitger created more than one hundred new organs, which set the highest quality. And with silvery rushing mixtures and the voluminous bass stops, it was not only perfectly suitable for the accompaniment in the church service but concurrently it offered the organists an opportunity for the interpretive mastery. And for that, a need grew, especially in the Hanseatic cities of the north, as the organs have been heard for the first time outside the church services, since the middle of 17thcentury. Franz Tunder (1614-1667) from Lübeck, the organist at St. Marien, regularly organized evening music sessions since 1646. The encouragement came not from the pastors, but from the music-loving merchants. Of course, they were also present in Hamburg, where the evening music sessions also found great approval. While other cities suffered from the horrors of the Thirty Years’ War, Hamburg protected itself by a modern wall system, skillful diplomacy and monetary payments. Thus, the citizens of the Hanseatic city were able to meet in their churches for evening organ concerts, where the visits were even free.

Johann Sebastian Bach was delighted with the organ in St. Katharinen

No wonder that in the baroque and later in the 19thcentury an enormously rich organ building and organ performing scenes developed in the Hanseatic city, which always remained in high level and attracted attention with technical innovations, such as the famous effect stops. Johann Sebastian Bach, for example, was overly excited with the organ in St. Katharinen. In 1720 he visited the city to play on this instrument and to apply for the position of organist in St. Jacobi. The fact that he was unsuccessful is one of the greatest cultural historical failures of the Hanseatic city. For Leipzig, however, it turned out to be a stroke of luck.

Soon it became known that the gifted organ builders of northern Germany offered a good business environment. Then came Hallenser Friedrich Stellwagen in 1629 as a journeyman of Gottfried Fritzsche to Hamburg, but then made himself independent in Lübeck, where he obtained considerable fame. From 1644 to 1647 he took over the reconstruction of the organ in St. Katharinen in Hamburg. From this outstanding instrument parts of historic pipes were preserved, which was able to be utilized by the Dutch company Flentrop Orgelbouw for the complete reconstruction in 2013.

Also, in the 19thcentury, when the sound ideal changed dramatically under the influence of late Baroque, Classicism and Romanticism, there were organ builders in Hamburg present, who built the instruments of the highest level.But orders were also received from foreign masters, such as the Itzehoe-based Johann Dietrich Busch, who built the organ in the Ottenser Christianskirche in 1744/45, or the company Marcussen & Søn from Aabenraa in Denmark. The organ built by Marcussen dates back to 1892 in St. Johannis Harvestehude, which was restored and expanded in 2013. The company Mühleisen from Leonberg (Baden-Württemberg) was able to preserve much of its historical record and equipped the organ with additional stops along with the most modern technology. Therefore, it combines a late romantic sound with the tonal possibilities of modern computer technology.

Many losses, but still more numerous new instruments

The need for instruments was always great, not only because old, damaged organs had to be repaired or replaced with the new ones, but also because of fire-related losses.

This was the case with the main organ in St. Michaelis, which fell victim to the flames twice: first time due to a fire caused by lightning on the 10thof March in 1750 and thereafter on the 3rdof July in 1906, when the baroque church completely burned down due to improper work on the roof. The Walcker organ, which was rebuilt in St. Michaelis and consecrated in 1912, was a case for the “Guinness Book of Records”, which was at the time nonexistent. With 12,173 pipes, it was the largest organ in the world. After the damage from the Second World War it was decided – although the instrument was preserved – that it would not be restored, but a completely new building would take place by the company Steinmeyer from Öttingen (Bavaria) with five manuals and pedal, 86 stops and 6,697 pipes. In 2009/10, the organ was renovated, but the sound quality of 1962 was preserved. In 2015 Johannes Klais from Bonn added chimes that encompasses 25 bells which enriches the instrument with a very special timbre. This large Steinmeyer organ can be played both from its own console and from the central console, which is located on the northern gallery. This has over five manuals. From these the combined 145 stops of the Steinmeyer organ, the Marcussen concert organ, and the echo organ can be played.

Old instruments and new sounds

The Great Fire in 1842 resulted in a loss of several valuable instruments, including the organs in the church of St. Nikolai and St. Petri. Even greater was the loss of organs during the World War II. Fortunately, the pipes of Schnitger organ in St. Jacobi had been removed at the time and therefore were retained, however the original housing burned down in 1944, when the blitz forced tower to crash into the nave. The so-called Organ Movement, which critically opposed the building of late romantic organs but oriented towards the early Baroque sound qualities made a huge influence in the 20thcentury in Hamburg. Thus, in the post war period especially, numerous organs of the 19thcentury were accordingly rebuilt, which brought greater change in their sound.

Yet the Hamburg company Rudolf von Beckerath broke into a new ground, both in terms of technology and sound, as well as sustaining the great baroque tradition. One of the most important works is the large organ in the major church of St. Petri, which was built in 1955 and restored and repaired by the Potsdam company Alexander Schuke in 2006. With four manuals, 66 stops and 4,724 pipes, it stands as one of the largest organs in Hamburg.

In the meantime, two trends were able to be observed in Hamburg, each determined by the historical conditions and current requirements. On the one side stood the reconstruction of famous instruments, such as Dutch company Flentrop with the already mentioned Baroque organ in St. Katharinen, using the partially preserved pipe materials. But on the other side, the construction of modern organs took place, with a wide range of sound possibilities.

Here is the organ in Elbphilharmonie, built by the organ maker Johannes Klais in Bonn. It consists of more than 69 stops with 4,765 pipes, and an echo organ with 4 stops, located in the ceiling reflector of the hall.

However, also in the reconstruction of historical organs there is often a contemporary extension of tonal spectrum, with the help of electronic mediums. This was the case with the romantic Marcussen-organ in St. Johannis in Harvestehude. The restoration was not only meant to recover the romantic richness of sound, but also to link the electronic sound generators, which opened up the new interpretative possibilities completely.

More organs than in Amsterdam and Venice together?

This diversity makes the Hamburg organ landscape, which of course is not limited to the actual urban area but beyond, so rich and attractive.

As the organs in this city have been developed, built and played almost continuously for many centuries, a tremendous variety of instruments have evolved, characterizing a lively and unique organ scene.

So, Hamburg is much more than a city of major port, shipping and trades. The Free and Hanseatic city probably possesses not only more bridges but also more organs than Venice and Amsterdam combined together.

Text: Matthias Gretzschel

Header photo: Adobe Stock/Jonas Weinitschke